TIME NY 1941

Out of the storm & strife of what Mexicans still refer to as "the revolution"—a confused and confusing mixture of banditry, adobe-hut Marxism, nationalism and agrarian reform which has been seething for 30 years—rose three great revolutionary artists. Their lurid propaganda paintings (reaching Mexico's illiterate peons far more effectively than printed words) covered walls from Nuevo Leon to Yucatan and revived the art of fresco painting on a scale unequaled since the Italian Renaissance. The three: stocky, effusive Diego Rivera; grim, brooding José Clemente Orozco; pallid, green-eyed, conspiratorial David Alfaro Siquieros.

When, under the Cárdenas Government Mexico's revolution cooled and solidified individualistic Old Bolsheviks Rivera and Orozco cooled off too. While Rivera disgusted with Stalinist politics, marched off to the U. S., Orozco moped off to Guadalajara to work on an angry, pictorial dirge called "Humanity Now." Stalinist Siquieros, always active in party politics, let his organizing and speechmaking interfere with his painting, ended up four months ago in the pentitentiary, accused of complicity in last May's Trotsky assault. Meanwhile many of Mexico's lesser and younger painters, secure in Government jobs under the Leftist-controlled Ministry of Education, took to turning out uninspired political cartoons and pictorial ads for the tourist trade.

There were also a few Mexican artists of ability who had never paid much attention to politics. Two of these last week had one-man shows in Manhattan. They were 48-year-old Carlos Merida, who painted cactus and Aztec idols before Rivera did and 32-year-old Expatriate Federico Cantú, who dwells in Greenwich Village.

Guatemala-born Merida, who for '14 years had painted nothing but abstractions inspired by French modernists during his visit to Europe, surprised Manhattan visitors to the Buchholz Gallery by a complete change of style. His perspectiveless, daguerreotypical canvases, brightly colored and surrealistically childlike, depicted toy hons and paper-doll-like human figures sedately waving the stumps of amputated arms. Critics were not sure that Painter Merida's new style was any improvement over the old, but found his ashy reds, yellows and blues loudly decorative.

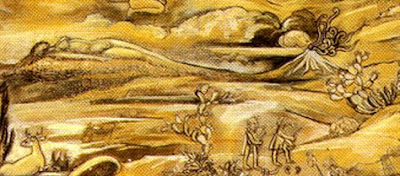

Baldish, roly-poly Federico Cantú, once an apprentice of Muralist Rivera, filled 57th Street's Guy Mayer Gallery more conventionally, with cactus, horses, ban-doleered soldiers and bedraggled peons. Best painting: a tropically rank portrait of Mexican Singer Aurelia Colomo (see cut), who carols tropically in the bar of Manhattan's Hotel Weylin.

Painters Merida and Cantú have done little fresco painting, but they are loud in their praise of Compatriots Rivera, Orozco, Siquieros. Says Merida: "They are three great painters, but the plastic expression of each is different. Diego makes politics in his pictures, Orozco is more poetic and lyric, Siquieros continues to be a great painter in spite of his politics." Cantú would have liked to do frescos, but says he got no commissions from the Mexican Government because he refused to paint Christ with the head of a donkey saints with the heads of pigs. "Although I am not very clerical," says he, "I do not go so far." Merida, who lives in Mexico City, and Cantú, who plans to return there soon, both hope that Mexico's President Avila Camacho will be partial to non-political Mexican art. Says non-political Artist Merida: "Painting makes its own politics, the artist doesn't need to mind politics. It is the land that speaks through my canvases, whether they are representative or abstract."